And it’s easy to see why. Hemp, the cannabis plant that does not produce THC, has a multitude of uses both historically and today. It can be used to make textiles, building materials, and livestock bedding. In modern culture, it also has the added benefit of being able to be used in bioplastics and, of course, potentially in health care.

In agriculture, it helps to maintain healthy soil by adding diversity to crop rotations, the practice of planting different crops in the same plot of land in order to improve soil health. Different plants deplete and return different nutrients into the soil. By rotating crops, agriculturists are able to maintain the best possible level of nutrients without adding synthetic compounds.

As cotton became more common place and part of American culture, mixed with the importing of other products, hemp production began to decline after the Civil War. However, as hemp fell out of vogue, interest in marijuana and its potential medicinal effects began to rise. In the United States, medical cannabis was used to treat nausea, rheumatism, and labor pain, and was available over the counter.

But by the 1930s, marijuana use became associated with Mexican and black communities, and politicians began to condemn it as a threat to poor, hard working Americans. In the era of the Great Depression, marijuana became linked with public resentment towards immigrants and the rising unemployment rate. By 1937, the Marijuana Tax Act made the plant illegal in the United States-both hemp and marijuana. In 1970 the Controlled Substance Act banned cannabis of any kind.

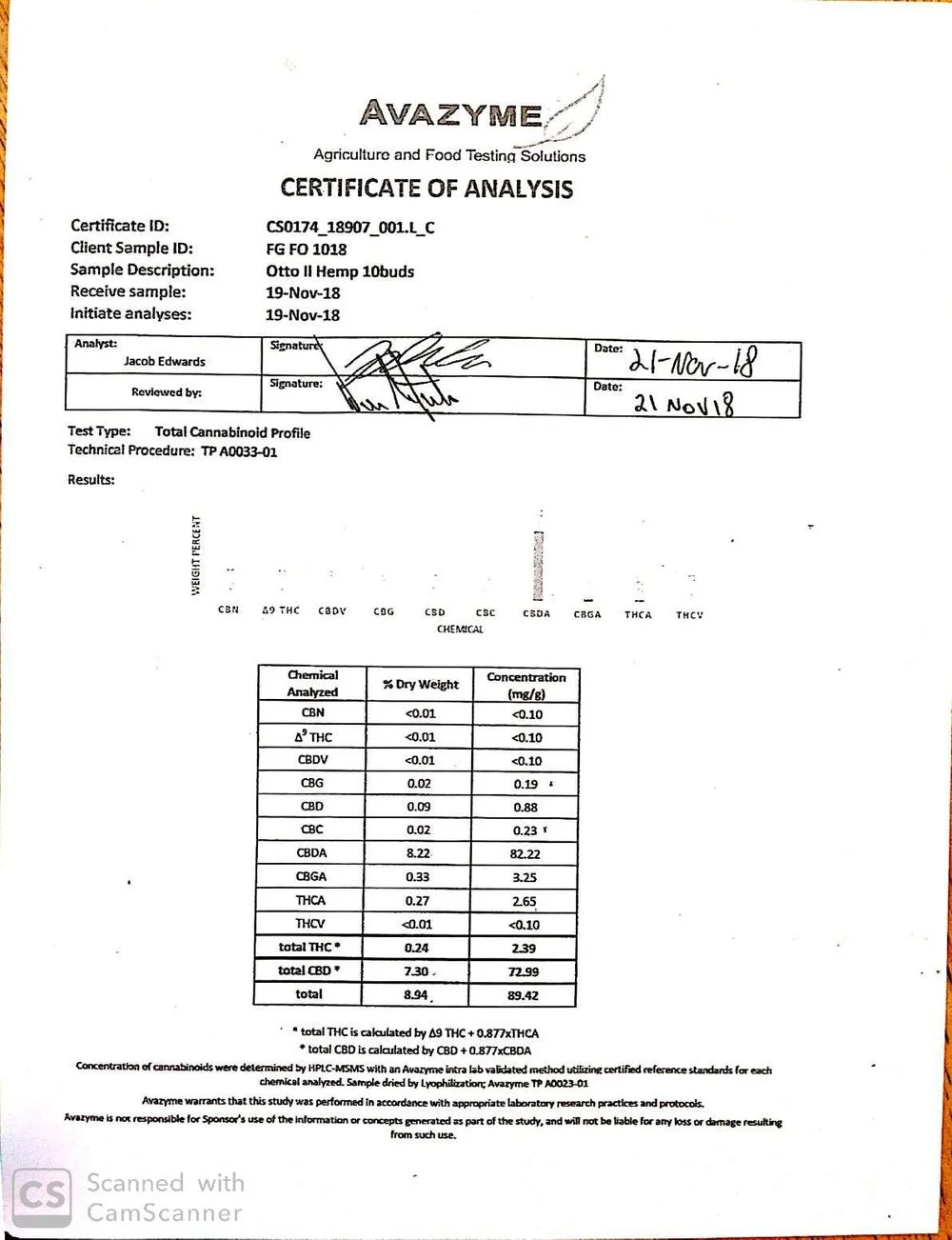

Fast forward to 2014, where a Farm Bill legalized hemp containing less than .3% THC to be grown for research purposes to study market-interest in hemp derived products. This past winter, another Farm Bill was passed expanding the 2014 Bill, allowing broad hemp cultivation and the “transfer of hemp-derived products across state lines for commercial or other purposes.”